The Antique Ideal: Between Formal Perfection and Veiled Eroticism

Long before it became a mere artistic motif, the male nude stood as a pillar of Western visual culture. In ancient Greece, nudity was not merely tolerated—it was celebrated as a sign of virtue, bravery, and harmony. The kouroi statues, depicting young men standing tall, are tributes to youth and masculine beauty. Yet behind the geometric perfection of the body lies the gaze—of the sculptor, the patron, the viewer: a gaze that admires, desires, and dreams.

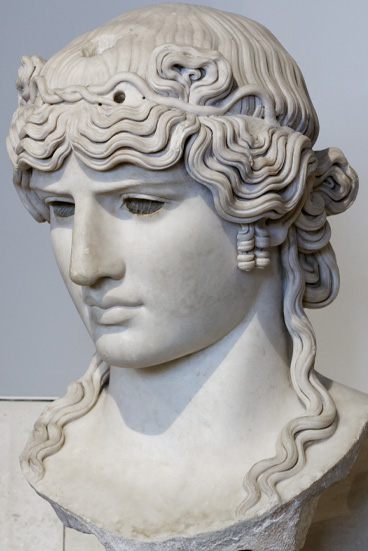

The Greeks themselves did not hide this gaze. Relationships between men, codified by pederasty, find echoes in art: Antinous, beloved of Hadrian and an icon of masculine beauty, stands as living proof of an acknowledged eroticism, even when wrapped in myth and symbol.

Similarly, the Apollo Belvedere (Vatican Museums) embodies this ideal of masculine perfection—divine yet sensual.

Renaissance and Academicism: The Male Nude as a Field of Experimentation

With the Renaissance, the male nude acquired new dimensions. It became the privileged ground for technical virtuosity, but also a space of freedom to express, under the guise of mythology, emotions and desires that were otherwise forbidden. Michelangelo, in the Sistine Chapel, populates the ceiling with powerful, athletic male bodies whose sensuality is unmistakable. His David, nude and triumphant, is as much a biblical hero as a declaration of love for virile beauty.

In the seventeenth century, Caravaggio paints a Narcissus entranced by his own reflection, or a languid Bacchus, whose pose and gaze invite a more intimate, more troubling reading. These works play with the boundary between admiration and desire, between the sacred and the profane.

The Nineteenth Century: Ambiguity Embraced

The nineteenth century witnessed the emergence of a more overt, though still coded, homoerotic aesthetic. Hippolyte Flandrin, with his Young Male Nude Seated beside the Sea (1836), offers an image of almost sacred purity, yet the solitude, the softness of the lines, and the vulnerability of the model touch upon the intimate. Admired by nineteenth-century homosexual circles, this painting became a silent manifesto: masculine beauty is no longer merely an ideal, but an object of contemplation, desire, and projection.

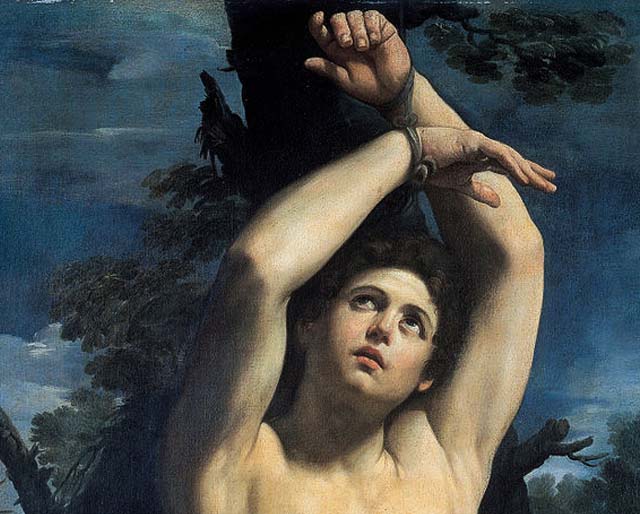

Saint Sebastian, the Christian martyr, is another central figure in this iconography. Bound and pierced by arrows, he becomes, under the brush of Guido Reni or Antonello da Messina, a symbol of suffering, but also of sensuality offered, of flesh exposed to every gaze. Here, classical painting reaches its zenith of ambiguity: it allows both artist and viewer to express, under the veil of the sacred, a fascination with the male body.

Symbols, Codes, and Strategies of Evasion

Confronted with moral and religious censorship, artists displayed remarkable ingenuity in evoking desire without ever naming it. Gestures, glances, composition, and the play of light became secret languages. A slipping drapery, a hand resting on a hip, a distant gaze—everything is a matter of suggestion.

Mythology provided the perfect pretext. The stories of Apollo and Hyacinthus, of Ganymede abducted by Zeus, of Patroclus and Achilles, allowed artists to explore tenderness, passion, and loss without ever descending into obscenity. Classical art thus invented a visual vocabulary of homoerotic desire—subtle, coded, yet powerfully resonant.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Today, these works are being rediscovered through the lens of queer studies and the history of homosexuality. They testify to art’s ability to transcend prohibitions, offering spaces of freedom and reverie to those who, for so long, were forced to hide. The classical male nude is not merely an object of aesthetic admiration: it is a mirror of desire, of history, of resistance.

The male nude in classical painting is far more than an academic exercise: it is a secret language, a space of freedom and desire, a mirror reflecting the dreams and passions of generations of artists and connoisseurs. Its rediscovery today allows us to do justice to a long-hidden history, and to admire, without subterfuge, the manifold beauty of the male body.